Mutant Blues! How to Modify the Minor Pentatonic Scale to Create Something New, Exotic and Twisted

How to modify the DNA of the beloved minor pentatonic scale to create a new, exotic, twisted musical species.

Push any rock guitar player into a corner, and it’ll be their command over killer minor pentatonic licks that’ll aid them in their fight to break free. In almost any modern musical situation, licks and melodies based on the minor pentatonic scale will fit unquestionably over any minor-key harmony and blend in with ease. When we play with these scales that we learned early on (they’re also played by many of our heroes when they’re at their most “real” and guttural), listeners feel comfortable with their simplistic construction (the scale is made of all of the “strongest” notes in the key) and their two-notes-per-string fingerings make patterns, riffs and licks relatively easy to play.

But what if you were to shift a note or two and come up with an innovative, uncharted, exotic, yet somehow familiar framework for untapped creative musical endeavors using basic ideas you’re already very familiar and comfortable with, but in an entirely new way? And what if each of those new frameworks had a unique, individual personality and musical power that could act on its own or be combined as a team to create a guitar-playing superpower? Enter the world of mutant pentatonics.

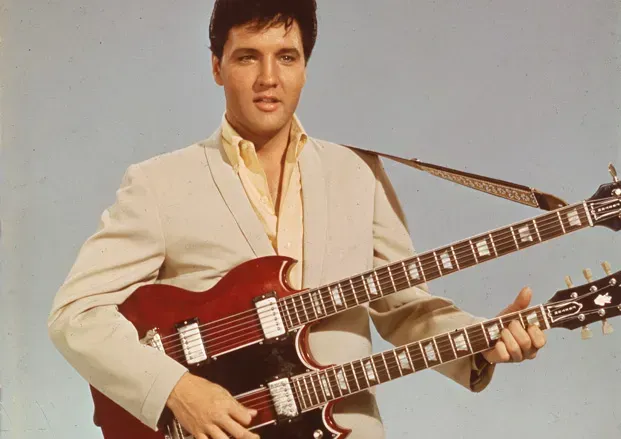

FIGURE 1 depicts the baseline template that our various evolutionary, or should I say “Frankenstein-ian,” offshoots will be built from, the D minor pentatonic scale, played in the standard 10th-position, two-notes-per-string “box” pattern. The scale is composed of the notes D (the root), F (the minor, or “flatted,” third), G (the perfect fourth), A (the perfect fifth) and C (the minor, or “flatted,” seventh).

Now let’s see what happens if we alter just one note. FIGURE 2 shows the same basic scale pattern, but with the minor third (three frets above the root) raised to the major third (four frets), giving it a bluesy, dominant sound. Players like Joe Bonamassa and Marty Friedman are fond of this sound, and Dimebag Darrell used the scale extensively in his solo on the song “Walk.” Try playing this “Mixolydian-pentatonic” scale over a dominant seventh chord with the same root.

[Be sure to check out the accompanying audio files for this lesson, which include the basic scale pattern for each figure, as notated here, followed by an improvised, "real-world" lead based on that same note set and fingering pattern.]

FIGURE 3 effectively describes the sound of the D Dorian mode (D E F G A B C) that is available with a different slight shift in the minor pentatonic box, substituting the major sixth (B, in this case) for the minor seventh (C). Use this pattern when you’re channeling Carlos Santana or Slash.

Our next example (FIGURE 4) is based on the blues scale, but instead of adding the diminished fifth, or “b5,” Ab, to the pentatonic scale, the b5 replaces the 5, setting up a more sinister but equally “open”-sounding five-note framework that is guaranteed to garner attention when used to set a mood. This scale, which I call D Locrian-pentatonic, is good for getting a menacingly dark, George Lynch- or Jeff Beck-type vibe. It also works great when played over a Bb7 chord in the key of D minor, as the Ab note becomes the minor, or “flat,” seven of that chord.

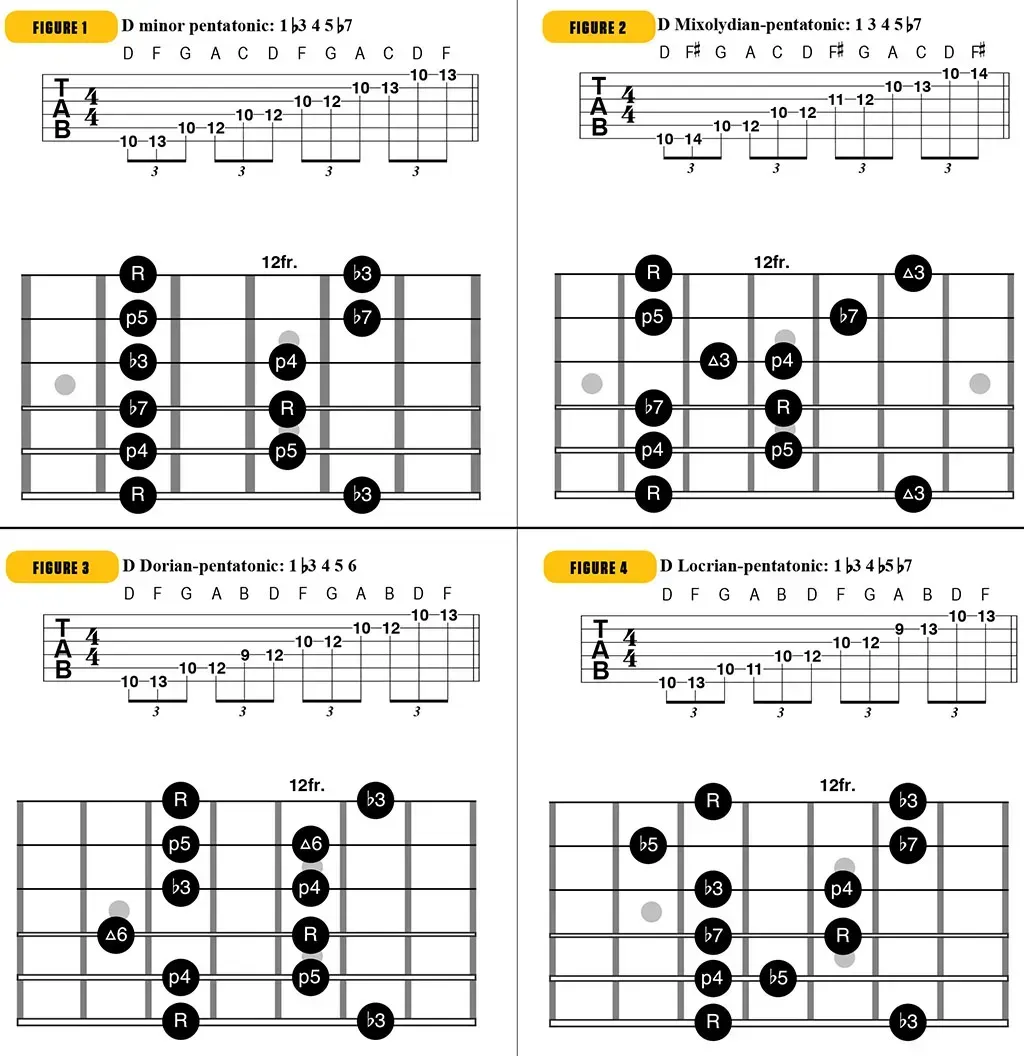

Moving in a more major direction, FIGURE 5 shifts our tonal center up a perfect fourth, to G, and channels the #4 sound of the Lydian mode (with the C# note), as well as the b7 of Mixolydian (via the F note). This doubly-mutated scale can more easily be seen as D minor pentatonic scale with a “flatted root” (C# instead of D). Try this five-note scale over a G major- or dominant-type chord when you’re looking for an exotic Lydian/Mixolydian feel, à la Steve Vai or Joe Satriani. Or use it to evoke the D harmonic minor scale with a slight twist and more open sound over a Dm or A7 chord. Coolness!

FIGURE 6 offers another, different double mutation to the original D minor pentatonic scale by raising, or “sharping,” both the D root and the minor third, F, a half step, to Eb and F#, respectively. The resulting note set (Eb F# G A C) offers a twisted, diminished seven- or altered-dominant-type sound may best be described as an “Yngwie Malmsteen acid trip.” Use it over an Eb or Eb7 chord, or just go crazy and shoehorn it in wherever and whenever you feel like playing something “outside.”

When acquainting yourself with all of these mutant pentatonic scales, try to stick with the five-note framework created by the new scale, even if it sounds a little “out.” Land on a note or phrase that is undeniably “inside” to follow up and create a feeling of resolution, and that lick will be instantly and memorably cool, if you play it with enough conviction! The concept here is to come up with fresh new licks that are based for the most part on comfortable and familiar pentatonic patterns that you already have a grasp on, with shifts to one or two altered notes and fingerings. For something frighteningly fascinating and useful, try integrating these transformed scale shapes and tonal feels with the patterns found in the badass Guitar World lessons by Glenn Proudfoot.

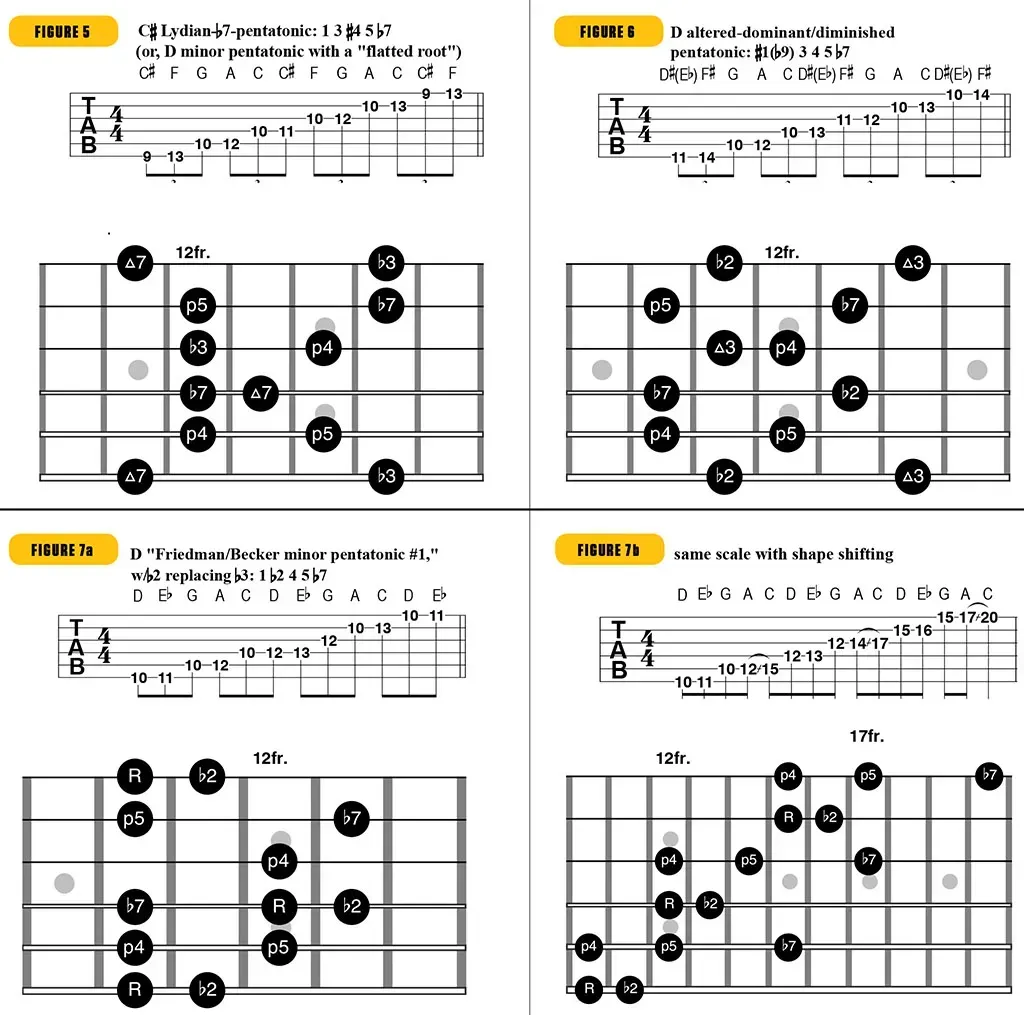

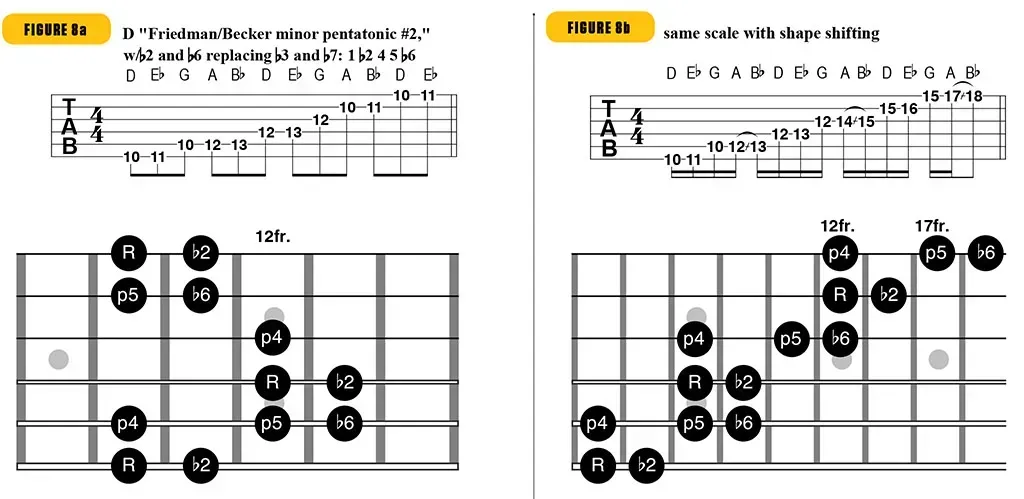

The journey into tampering with the DNA of the pentatonic scale has just begun, though. To inspire the mad scientist in you to come up with your own ideas for crafting your own five-note scales and show you some other things to do to manipulate their mutation, FIGURES 7a and 8a chop up the intervallic “comfort” of the original D minor pentatonic scale’s structure by substituting the b2, or b9, for the b3, providing a wider leap between scale tones and creating a completely unique and enigmatic mood.

FIGURES 7b and 8b present the scale using the same left-hand shape shifting over octaves with the different connecting scale tones (the b7 and b6, respectively) creating entirely new feels. You can hear lots of this type of exotic, twisted soloing on the brilliant early recordings released by Marty Friedman and Jason Becker in the Eighties.

Experiment with your own variations on these patterns, and try transposing them to different keys, tonal centers and areas of the fretboard. This lesson only scratches the surface of the possibilities you’ll find lurking in all of the small moves you can make to come up with your own pentatonic scale mutations. Happy shredding!