10 Commandments of Playing Guitar in the Style of Pantera's Dimebag Darrell, Part 1

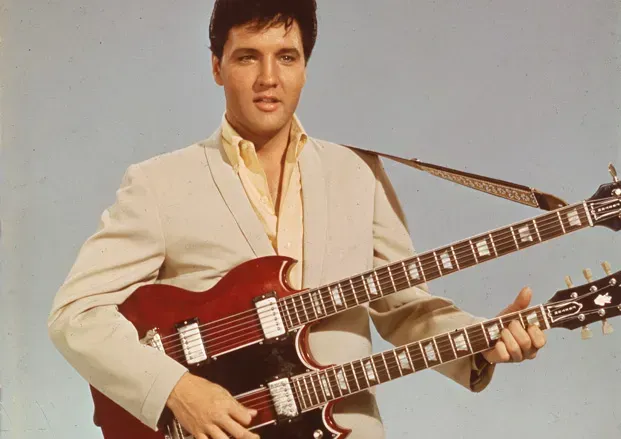

Commandment 1: Honor Thy Van Halen

... and ZZ Top, Kiss, Judas Priest, Black Sabbath, Ted Nugent, Pat Travers, early Metallica (Kill ‘em All, Ride the Lightning, Master of Puppets) and Randy Rhoads. Van Halen’s impact on Dimebag’s playing is unmistakable. The “vibe” of early Van Halen is by far the most recognizable influence in Dimebag’s playing. From the grooving rhythms played like leads of their own, to the tone, to the phrasing in his lead playing, Dimebag took the inspiration of Edward Van Halen and forged his own identity.

Pieces such as “Eruption” and “Spanish Fly” were favorites of Dimebag, who would play them in his unaccompanied guitar solos back in Pantera’s early club days. Dime has been noted as being Texas’ “Van Halen clone,” the local hotshot who could play all of the most impressive licks of his hero. Further, the brotherly bond of the Van Halen brothers (Eddie on guitar and Alex on drums) was mirrored in Pantera (Vinnie on drums and Dime on guitar).

Van Halen’s impact is further felt as the words “Van Halen” were actually Dimebag’s last words spoken before he was tragically murdered. “Van Halen” was something Dime would say to his brother Vinnie before a live performance to inspire them both to play a fun, lively, rocking show. Also, Dime was actually buried with the guitar that inspired him most—Eddie Van Halen’s yellow and black striped guitar featured on the back cover of Van Halen II. To truly understand Dimebag’s playing, it is crucial to absorb the “Van Halen” feel, as well as the techniques and attention to tone that were such a part of the early Van Halen experience.

Commandment 2: Thou Shalt Use the Major 3rd

Always wearing his Van Halen influence on his sleeve, Dimebag was never one to shy away from using the interval of a major 3rd in his heavy playing. Shunned by most “metal” players, the major 3rd was an essential tool in Dime’s bag of tricks. When playing in E (minor), the major third is G#, which adds a unique feel to riffs and licks that also utilize the minor 3rd (G).

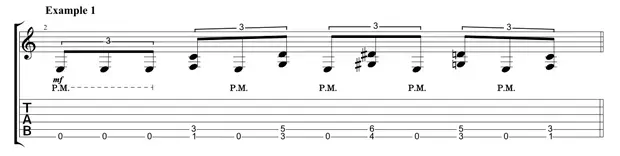

Theoretically, this major 3rd lends lines a Mixolydian quality, though it essentially gives a bluesy type of sound and adds tension/dissonance to minor key tonalities (For more information, check out Guitar Strength Volume 1: Mastering the Modes.) EXAMPLE 1 is a Dimebag-inspired riff using this major 3rd in a minor key.

Notice also how Dime gets extra mileage out of the interval by using it in a pattern that also makes use of the flat 9 (F in E minor). EXAMPLE 2 is another Dimebag-inspired riff using the same intervals. (For another riff using the major 3rd, which was clearly an influence on Dimebag, check out the end of “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath” by Black Sabbath.)

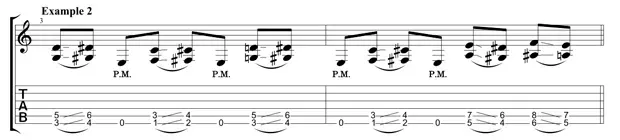

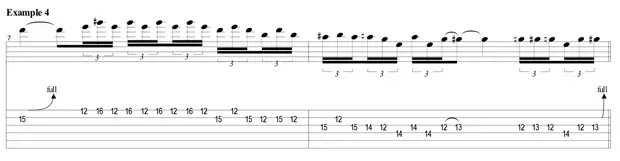

The major 3rd was not just essential to Dimebag’s riffs, it was also extensively used in his lead playing. EXAMPLE 3 is an E minor fingering of the “Dimebag Scale,” a minor pentatonic scale with the addition of a flat 5, major 6th (omitted on the A string and used only on the B string, 14th fret for ease of fingering), and major 3rd.

The major 3rd was not just essential to Dimebag’s riffs, it was also extensively used in his lead playing. EXAMPLE 3 is an E minor fingering of the “Dimebag Scale,” a minor pentatonic scale with the addition of a flat 5, major 6th (omitted on the A string and used only on the B string, 14th fret for ease of fingering), and major 3rd.

When attempting to conjure the influence of Dimebag in your own playing, experimentation with the integration of this major 3rd into more “standard” minor phrases is highly encouraged. Don’t be afraid of sounding “happy”; play the note like you mean it and you’ll be amazed at its versatility and its ability to make your playing substantially more interesting.

Commandment #3: Embrace Symmetry

Another Van Halen-inspired technique employed by Dimebag was the use of symmetrical fingerings. This technique is extremely easy to learn but requires taste and skill for successful implementation. To perform this technique, simply devise a fingering shape on one string and apply it across all six. EXAMPLE 5 is a Van Halen-esque lick, based on a root, major 3rd, 5th shape in E, continuing down to the A string and resolving on a B string bend from D to E (and back down to D for some minor 7th tension).

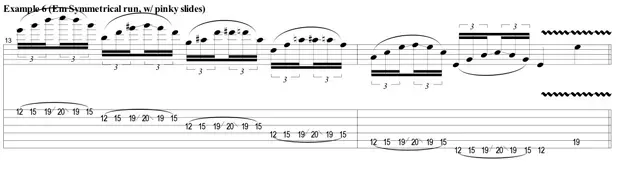

Clearly inspirational to Dime, EXAMPLE 6 is a variation in the same (12th) position, this time using the minor 3rd (G), 5th (B), and a slide to and from the flat 6th (C). This expanded symmetrical shape still uses a simple 1-2-4 fret hand fingering across all six strings, yet the pinky slide gives it some extra range and movement.

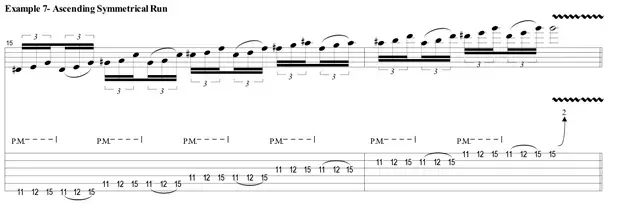

Further examples of simple, yet effective symmetrical patterns used by Dimebag can be seen in EXAMPLES 7 and 8. EXAMPLE 7 is another shape, this time using the major 7 (Eb in E), the root (E), and the minor 3rd (G) as its basis. In this case, the pattern is an ascending climb combining both picking and legato phrasing, again using the 1-2-4 fingering.

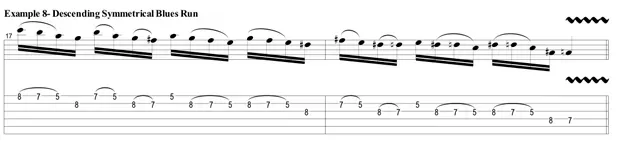

In EXAMPLE 8, which is based on one of Dimebag’s favorite patterns, the shape uses a 4-3-1 fingering in a descending sequence on the top three strings. This shape in this position is a throwback to the playing of Pat Travers, and can be quite effective when playing over rhythms in A minor and E minor.

Feel free to transpose it into other keys and use it often, just as Dime did. It is important to notice that though Dimebag possessed astounding picking technique, he tended to favor executing most of his lines in a legato fashion (another homage to Mr. Edward Van Halen). Dimebag’s love of legato gave his lines a fluid, lively quality, and his powerful left hand technique was extremely important when effectively implementing these symmetrical patterns into his lead licks.

Commandment 4: Give Chords New Found Power

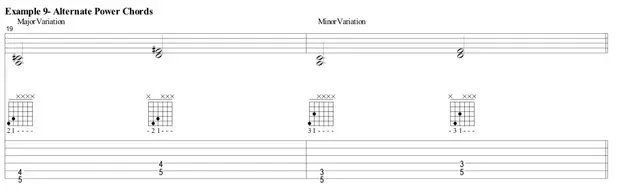

Never content with “standard” guitar techniques, Dimebag was an avid user of the “other” power chords. Instead of relying on normal root-5th and root-4th (inverted 5th) power chords (though he was an obvious master when it came to using them), Dimebag would often come up with and use alternative dyads (two-note chords) in place of standard power chords. These chords were usually major or minor thirds stacked on top of the root. EXAMPLE 9 is the two basic versions of these chords with 6th and 5th string roots. The first is the “major 3rd” variation and the second is the “minor 3rd” version.

EXAMPLE 10 is a figure using the minor 3rd power chord. Notice how the chords act to add texture and movement to the riff, as they work well when used in the same riff as the more pedestrian root-5th power chords. The chords also add a nice tension, as they are not as “homogenous” and “neutered” sounding as the standard root-5th chords. Also, when used with a rocking distorted tone, these chords have an extremely powerful sonic fingerprint with their unique overtones.

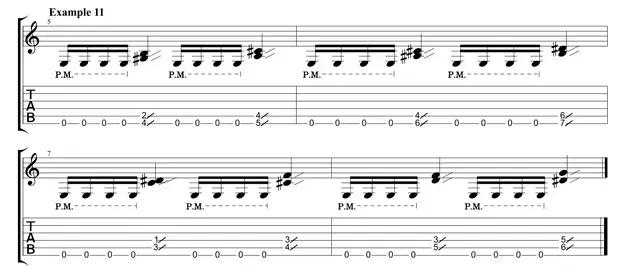

These overtones are, in fact, what makes these chords so special and useful. With usual major or minor chords and triads, playing them with distortion often results in a cluttered, un-musical noise. There is just too much information present to allow sonorous, musical sounds when using the standard major or minor chord shapes. However, by just playing the root and 3rd, a vibrant, tense, rich sound is created, really putting the “power” in power chord. Experiment often with substituting these root-3rd power chords for standard root-5th chords in your riffs. Also, try varying your usage of major and minor 3rds, as often times the “wrong” (out of key) 3rd will sound most interesting in a riff. EXAMPLE 11 is a Dimebag inspired riff using these harmonically “wrong” power chords.

Commandment 5: Know your Nodes

No discussion of Dimebag would be complete without mentioning his penchant for playing with harmonics. Dimebag’s playing was peppered with any and every type of harmonics: natural, artificial, tapped, etc. Playing with an overtone-rich, distorted sound, harmonics (whether naturally or artificially produced) are an integral component in the beast of electric guitar. Harmonics can occur almost anywhere and can be produced by a myriad of means, and can occur many times as an accidental consequence of playing with a loud, distorted sound.

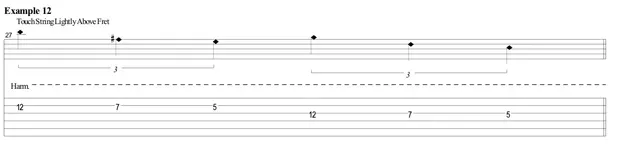

Dimebag, however, excelled at controlling the beast, and was able to skillfully use harmonics as one of the most expressive elements in his playing. To understand how Dime would use harmonics, we’ll first look at the naturally occurring harmonic nodes that occur across the fretboard. EXAMPLE 12 is a basic depiction of the most common, “easy” harmonics that occur when a fret hand finger is used to lightly touch a plucked string (without actually pushing it down and fretting it) and produce a harmonic.

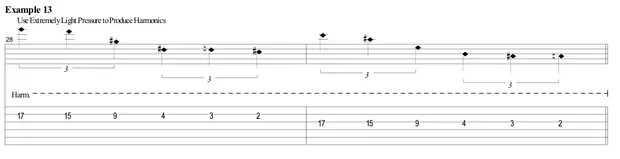

EXAMPLE 13 shows some more difficult to produce harmonics along the same string, many of which were used extensively by Dime.

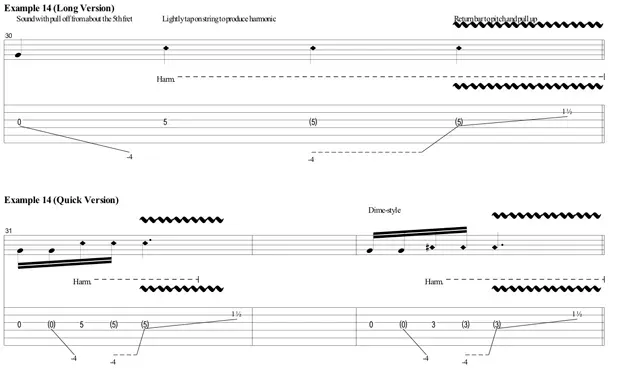

Dime was never content to just play the harmonics, though, as he would often use a variety of techniques to produce and manipulate them. The most famous of these techniques was Dime’s signature “harmonic scream” technique. The basic maneuver is depicted in EXAMPLE 14.

To perform this technique as Dimebag would, a floating tremolo bridge (able to bend a note below and above) is necessary (preferably a locking Floyd Rose or its equivalent). First, get the string moving by “plucking” it with a silent fret hand pull-off while simultaneously dumping/depressing the bar and bending the tremolo down. As the open string is lowered in pitch and its tension is reduced, lightly tap the selected harmonic node with the fret hand “bird”/middle finger. Next, after the harmonic has been sounded, slowly return the bar to pitch, pull it up higher, and apply vibrato with the whammy bar. Note that the actual time the open/dumped string rings is only a fraction of a second, it is only sounded so as to allow the string movement enough to produce the fret hand “tapped” harmonic.

Also note the importance of fret hand muting, being sure to use the fret hand thumb (wrapped over the top of the neck) and fret hand fingers to mute any unwanted noise from the unused strings. Experiment with different harmonic nodes, as some will be easier to execute and some will sound more interesting than others. While Dimebag was also quite adept at using Zakk Wylde/John Sykes/George Lynch/Billy F. Gibbons-style “pings” (artificial harmonics, A.K.A. pick harmonics) he was especially adept at using multiple, combined harmonics as a way to spice up his rhythm playing. EXAMPLE 15 shows this technique at play.

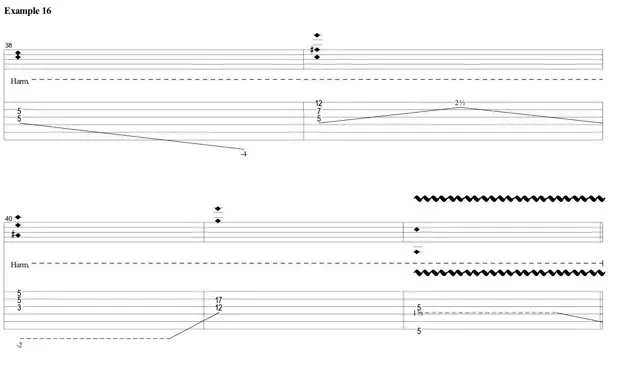

Notice first that Dime loved using “in-between” harmonics, those that had a particularly shrieking/squealing sound. Also notice that in combining two or more harmonics, an extremely cool set of screaming, dissonant overtones is created. Try any and all combinations of harmonics on various string sets and at various node points, and also experiment with manipulating the combinations with your whammy bar and/or effects pedals. EXAMPLE 16 is several available combinations.

The possibilities are endless. Check out Part 2!

Scott Marano has dedicated his life to the study of the guitar, honing his chops at the Berklee College of Music under the tutelage of Jon Finn and Joe Stump and working as an accomplished guitarist, performer, songwriter and in-demand instructor. In 2007, Scott developed the Guitar Strength program to inspire and provide accelerated education to guitarists of all ages and in all styles through state-of-the-art private guitar lessons in his home state of Rhode Island and globally via Skype. Visit Scott and learn more at www.GuitarStrength.com.